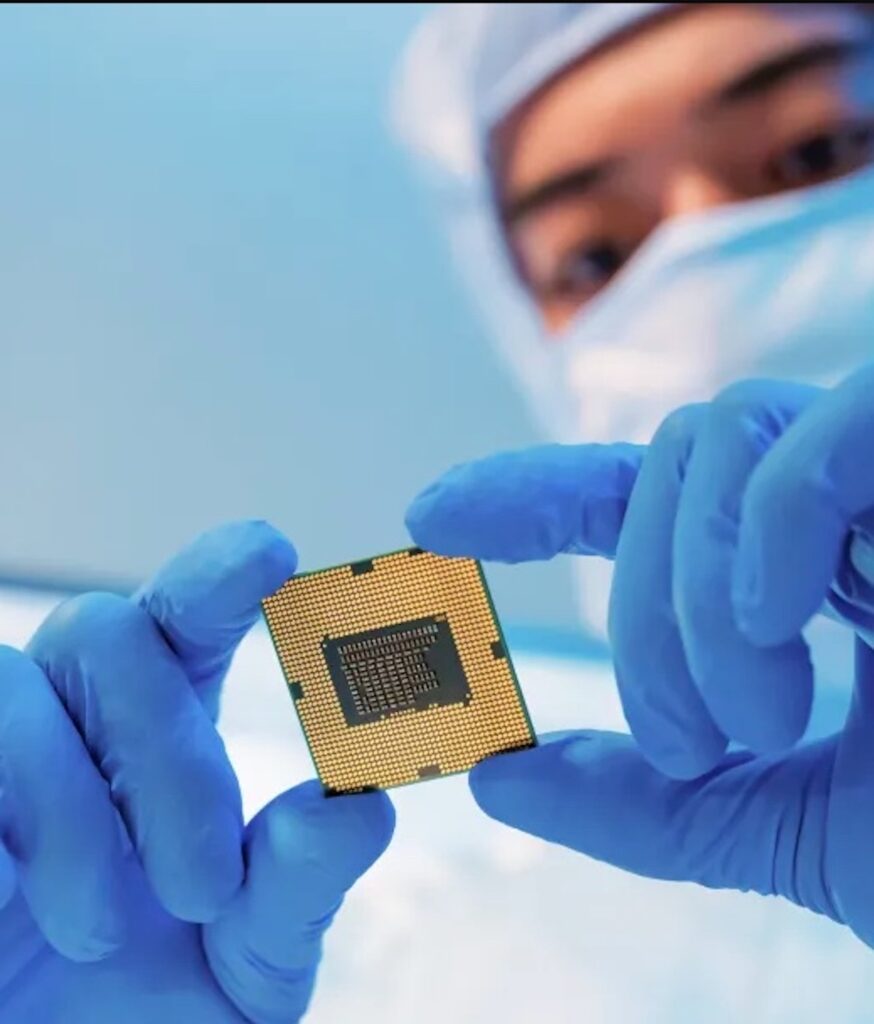

Chip shortage: Who will win the chip challenge? The question is worth billions of dollars of investment for Europe and the U.S., engaged in a wild race to beat Chinese supremacy. The U.S. and E.U. have specifically channelled nearly $81 billion toward producing the next generation of semiconductors, intensifying a global clash with China for chip dominance. This is the first wave of nearly $380 billion allocated by governments worldwide for companies such as Intel Corp. and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. to ramp up production of more powerful microprocessors. The surge has pushed the Washington-led rivalry with Beijing over cutting-edge technology to a critical tipping point that will shape the future of the global economy.

The chip shortage that exploded in the post-pandemic era highlighted the importance of these tiny devices to economic security. The stakes in the semiconductor rivalry are now on everything from revitalizing U.S. technology production to asserting an edge in artificial intelligence to balancing peace in the Taiwan Strait.

Chip, so the USA challenges Beijing

Spending on chips by the United States and its allies marks a new challenge to Beijing’s industrial policy, although it will take years to bear fruit. The influx of funding has strengthened the battle lines in the U.S.-China trade war, including in places like Japan and the Middle East. It also gives a lifeline to Intel, the former global chipmaking leader that has lost ground to rivals, including Nvidia Corp. and TSMC, in recent years.

The investment plans have reached a pivotal moment in the United States, where officials last month made public $6.1 billion in grants for Micron Technology Inc., the largest U.S. maker of computer memory chips. It is the latest multibillion-dollar grant for an advanced facility, crowning a series of commitments approaching $33 billion to companies including Intel, TSMC and Samsung Electronics Co.

President Joe Biden has opened the funding spigot with his signature 2022 Chips and Science Act, promising a total of $39 billion in subsidies for chipmakers, plus loans and guarantees worth an additional $75 billion, plus tax credits of up to 25 per cent. It is at the heart of his attempt to revive domestic semiconductor production-particularly cutting-edge chips-and create a wave of new factory jobs to convince voters he deserves re-election in November. These investments by the United States seek to do more than simply counter China. They also aim to bridge the gap with decades of Taiwan and South Korean government incentives that have made these places centres of the chip industry.

How much is Europe investing in semiconductors?

Across the Atlantic, the European Union has put together its $46.3 billion plan to expand local manufacturing capacity. The European Commission estimates that public and private investment in the sector will amount to more than $108 billion, mostly to support large manufacturing sites. The two largest European projects are in Germany: a planned Intel factory in Magdeburg worth about $36 billion and receiving nearly $11 billion in subsidies and a TSMC joint venture worth about $11 billion, half of which will be covered by government funds.

Even so, the European Commission has not yet given final state aid approval to either, and experts warn that the bloc’s investments will not be enough to meet the goal of producing 20 per cent of the world’s semiconductors by 2030. Other European countries have struggled to finance large projects or attract companies. Spain announced in 2022 that it would allocate nearly $13 billion to semiconductors. However, it has only distributed small sums to a handful of companies due to the country’s lack of a semiconductor ecosystem.

India, Saudi Arabia and Japan enter the chip challenge

Emerging economies are also seeking to enter the game of semiconductor dominance. India in February approved $10 billion in government-funded investments, including a bid by the Tata Group to build the country’s first major chip manufacturing plant. In Saudi Arabia, the Public Investment Fund is targeting an unspecified “substantial investment” this year to kick-start the kingdom’s foray into semiconductors as it seeks to diversify its fossil fuel-dependent economy.

In Japan, the Ministry of Commerce has secured some $25.3 billion for its chip campaign since its inception in June 2021. Of this sum, $16.7 billion has been allocated for projects, including two TSMC foundries in southern Kumamoto and another foundry in northern Hokkaido, where Japan’s local products are produced. Rapidus Corp. aims to mass-produce 2-nanometer logic chips in 2027. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is targeting a total investment of $64.2 billion, including sums from the private sector, with the goal of tripling domestically produced chip sales to about $96.3 billion by 2030.

How strong is China?

Some experts argue that China is years behind, while others insist that the world’s second-largest economy is on the verge of catching up in the chip arena. China now has more semiconductor plants under construction than anywhere else in the world, accumulating the expertise needed for a domestic technological leap. It also works on domestic alternatives to Nvidia’s AI chips and other advanced silicon. The amount of money Beijing is pouring into the industry probably puts US spending to shame. According to estimates by the Washington-based Semiconductor Industry Association last week, China was on track to spend more than $142 billion. As part of that effort, the government raised an additional $27 billion for what is known as the Big Fund to oversee state investments in dozens of companies, including local chip-making champions Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp. and Huawei Technologies Co.

Another sign of Beijing’s determination comes from corporate filings in China. According to a Bloomberg News analysis of hundreds of companies in the official Tianyancha corporate database, there are more than 200 semiconductor companies in the country with a registered capital of more than $61 billion. Much of this comes from state-affiliated entities, which should translate into real capital employed.