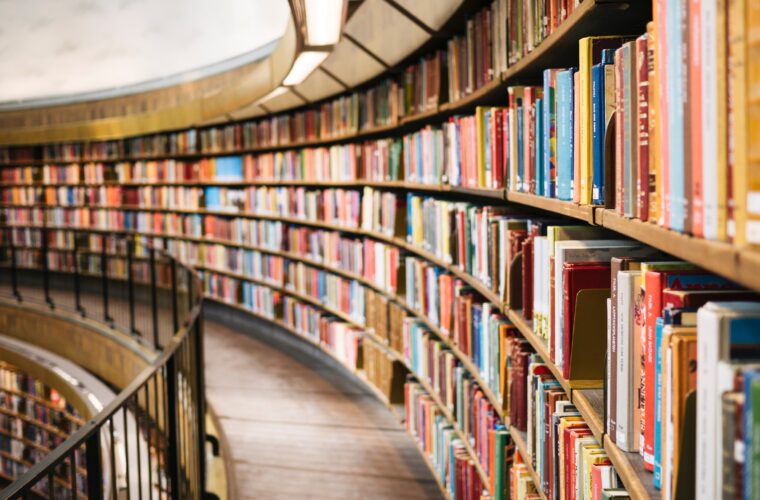

More books are being sold now than five years ago. Per Wordsrated, the international sales of published books were US$129 billion as of June 2023, about a US$7 billion increase compared to 2018. The research group expected the market to grow to over US$160 billion by 2030, rising by almost 2 per cent yearly. These sold books include paperback and e-book formats, a type of book people can read using mobile devices or online platforms, such as Amazon.

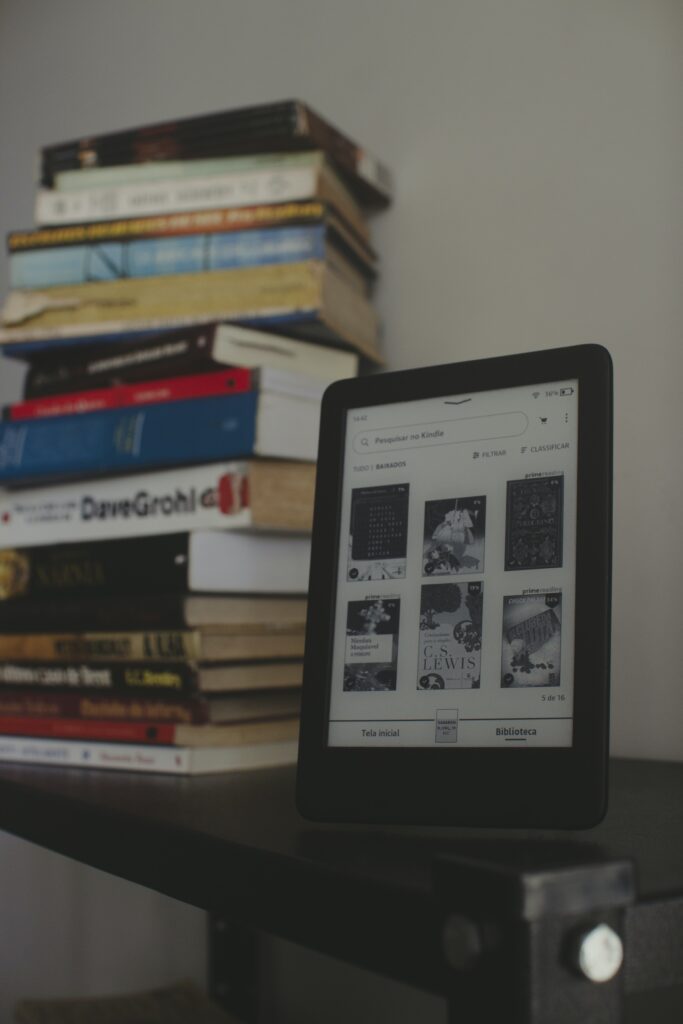

It is easy to assume that technological development has led to the broader distribution of e-books and increased sales, but that is not the case. The market share of e-books compared to paperbacks is smaller. Roughly speaking, one e-book is sold when four hard paper books are sold worldwide.

Although market expectations remain positive for e-books, reports say that even many digital-native generations, such as Gen Z or Gen Alpha, seem to be more drawn to paper books over electronic counterparts.

Would there ever be a chance for e-books to win in the book-selling race?

E-Books: Where and How Did It Start?

1971 was a big year for techies – it was the year when the first email between two individuals was exchanged, and the first e-book was distributed online. American writer Michael S. Hart initiated Project Gutenberg, distributing public domain books and text workers on the internet, establishing a digitised library. The inventor of the e-book typed and registered the country’s Declaration of Independence.

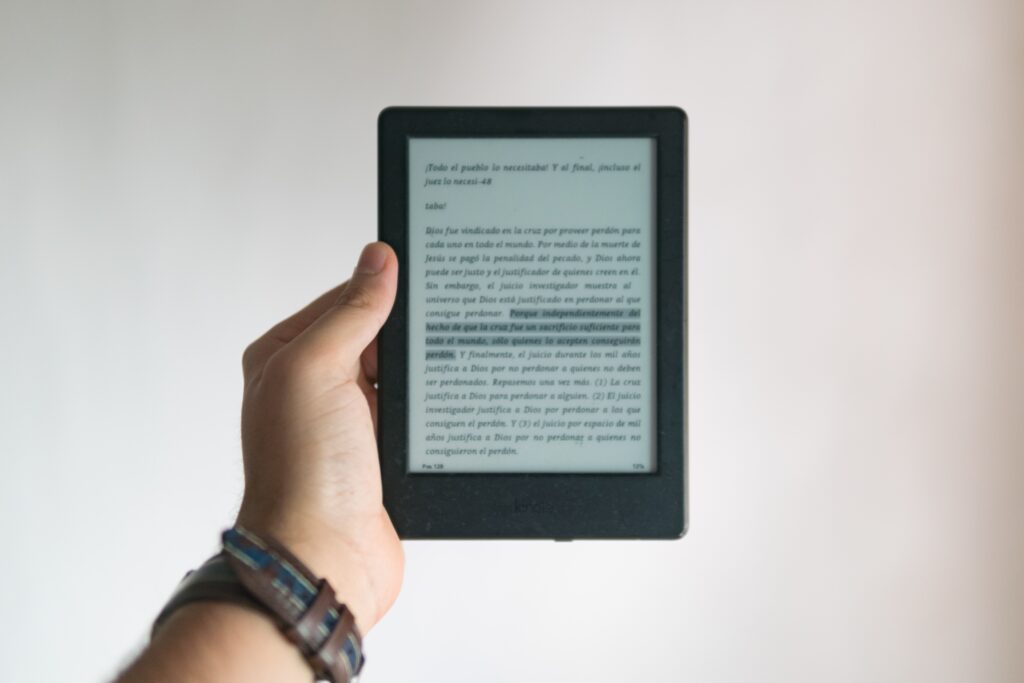

The introduction of a digital device whose sole purpose is to improve the reading experience happened over two decades after that. Until the late 1990s, people had been reading digitised text files, such as words and pdfs, on their computers. Mobile phones with text viewers were less widespread than they are nowadays.

The very first e-book reader, or e-reader, was launched in 1998. American inventors and lifelong readers Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning were the ones who came up with the idea to build a mobile reader for e-books. The developers’ invention was named the Rocketbook. It was when electronic ink was not available, so the book had an LCD screen with a transflective display, an optical layer that could reflect light. The first reader was heavier than modern e-readers. About 500 grams, while the latest Kindle model from 2022 is less than 200 grams. The book could store up to 10 books and run for a maximum of 20 hours.

RocketBook: The very first E-Reader

The two developers pitched the idea to Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon, before commercialising the Rocketbook. Bezos, who first did not pay much attention to the product, seemed more intrigued when the developers showed the prototype to the Amazon chairman in late 1997. Still, the prototype needed several improvements, including wireless computer connectivity and enhanced readability. The device had to be plugged into a computer to download digital copies and was not using e-papers or e-ink due to cost or reliability issues.

After discussions, Eberhard and Tarpenning joined hands with American bookseller giant Barnes & Noble for more fundraising opportunities. The first commercial model of the Rocketbook was out in 1999 and sold 20,000 units at a retail price of US$499. As of 2023, more companies have participated in the noble cause to digitise people’s reading experience backed by e-readers with the help of e-ink or e-papers, notably led by the Kindle series from Amazon. Besides American companies, Toronto-based Kobo Inc. has the Kobo e-reader series. Seoul-based bookseller Yes 24’s Crema, and RIDI’s RIDIPAPER are some prominent e-reader developers.

E-Books Over Paperbacks?

There were over 930 million e-book users across the world per a 2022 estimate, with expectations to increase until 2027. According to a 2021 survey, more than 40 per cent of people between 18 and 29 years old had read digital formats in the last 12 months in the United States, making teenagers and people in their 20s the biggest user base of e-books and e-readers.

One of the biggest advantages of e-books compared to paperback books is easy access. People can find and download copies as long as their devices of any kind are connected to the internet, from computers to mobile phones. The development of smartphones would have contributed to improving access as well, with iOS or Android-optimised e-reader apps.

Low cost is another reason that attracts more readers to buy digital options. Booksellers often provide digital formats of hardcovers at a cheaper price, on an average of US$7 per title as of 2023. This is possible as publishers and sellers can save the cost of production or delivery of books. There also are subscription plans of retail platforms through partnerships with publishers, which allows e-book readers to try more books at a lower cost.

Reasons for the e-book market growth can be found outside of e-book platforms, too. Environment organisations and governments often promote digital options over traditional paperbacks, as it uses less energy and resources to produce and distribute the books. COVID-19 also played a role in the expansion of the market. A 2022 report says that the sales of e-books dramatically increased during the pandemic period due to shipping delays of online retailers and fear of possible infection from hard copies obtained from libraries or bookstores.

Hard Covers Strike Back

The worldwide sales, or revenue, of e-books is expected to grow until 2027, from US$13.5 billion in 2022 to US$15.3 five years later. However, the income per capita may not show a similar trend. The average revenue per user has steadily decreased from US$16.3 in 2017 to US$14.5 in 2022.

Part of this gap between general and per capita growth comes from little difference in the prices of digital and physical products. For famous authors or bestselling books, platforms would charge almost the same price for both hard and soft copies, even though digital options have far fewer manufacturing and delivery fees. Statista explains that this decreases the market’s growth potential, although more and more people are turning their eyes to e-books.

Hard Covers over E-books?

Moreover, the primary readership, Gen Z and Gen Alpha, are slipping through the pages of digital copies with the recent retro boom. Reports say that younger generations who are used to reading and watching media on digital displays find novelty in reading old-fashioned hardcovers. Reading physical books is also a different, more tangible experience as it allows readers to hold books, pinch paper pages, and smell, which is impossible in digital formats.

A sense of permanent ownership can be another factor for people to choose paperback books over digital. As seen in the case of the closure of Microsoft’s e-book store in 2019, e-books can disappear with service providers when the platforms decide to end their business. Buyers may not have full ownership of the bought copies unless the soft documents are saved on personal devices as files independent from such providers. On the other hand, physical books can be theirs forever once they purchase them.

Sometimes, technology cannot be the solution to everything and everyone. Some analogue items remain strong, staying golden despite the emergence of digital competitors, like hard copies at your local bookstores.