For the first time in 22 years, Japan successfully launched the next-generation rocket on February 17. The rocket inserted two satellites into orbit, overcoming the country’s failed launch attempt from a year ago.

The launch of the 57-metre, 422-tonne rocket took place at 9:22 AM at the Tanegashinma Space Centre, around 1,000 kilometres away from the capital city, led by the manufacturer Mitsubishi Heavy Industries under the supervision of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA).

As a test operation for commercial users, the launch paved the way for Japan to prove its competence in the space launch business, a highly competitive industry dominated by market leaders like SpaceX. According to JAXA, the rocket launch was “reliable and accurate”, putting two small satellites less than a kilometre away from the targets.

More about Japan’s H3 Rocket Project

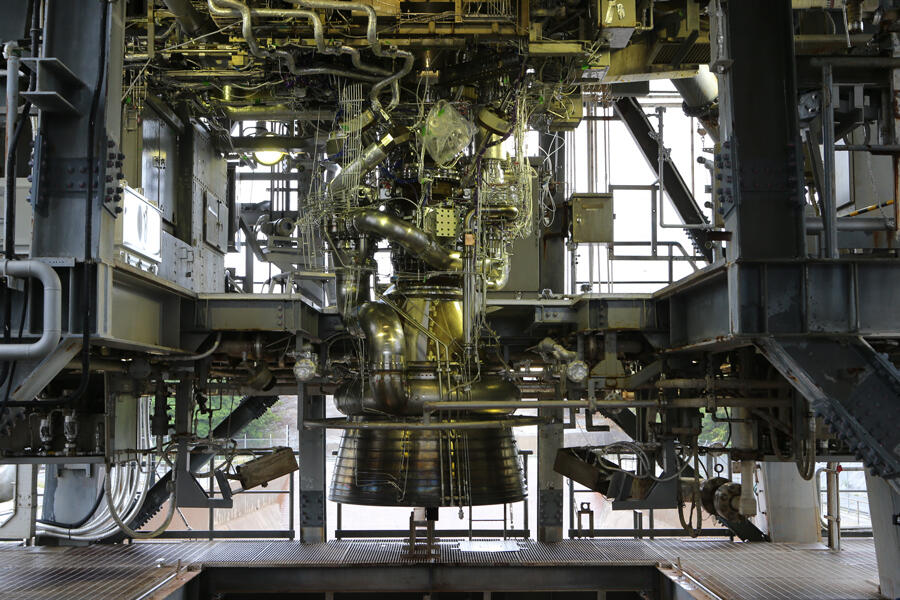

The H3 is JAXA-MHI’s project to introduce a commercial launch business by developing two-stage, liquid-propellant rockets. It is a successor of MHI’s main rocket model, H-2A, which is set to retire soon after the 50th unit launch.

H-2A has been known for its high launch success rate of 98 per cent, failing only once for the sixth unit. Regarding the price level, the model falls behind other Chinese or American competitors due to the high launch price in the global market.

Compared to H-2A, the latest model of the H3 rocket’s propulsive force is 40 per cent stronger, and the launch cost is almost half, 5 billion yen (US$ 33 million). Slashing launch costs is to make the rocket more competitive in the global market by providing a cheaper price level against its competitors. SpaceX’s Falcon 9, for example, reportedly offers a price of over US$ 62 million for a single-use rocket and US$49 million for a reusable vehicle.

The first test flight of the H3 rocket happened on March 7 2023, which failed due to an error that stopped the ignition of its second-stage engine. JAXA and MHI replaced the land observing satellite-3 payload that the first unit carried with a 2.6-tonne dummy and two small satellites for the second unit. The small satellites are Canon Electronics’ optical observation satellite, which weighs 70 kilograms, and an infrared imaging satellite of 5 kilograms.

To the press, MHI said that it will oversee rocket launch operations, aiming to do six launches a year.

Government’s push for the growth of the space industry

Until the mid-2010s, the Japanese government did not pay much attention to space-related projects. Space start-ups had a hard time securing funds and clients, and big satellite builders like Mitsubishi Electric Corporation did not show much interest in them either.

The change in the government’s attitude with then-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s announcement in 2018, making more investments in the country’s commercial space industry and reaching a market size of US$ 21 billion by the early 2030s, doubling what it was back then.

Some of the main policies that the government has been supporting besides the rocket developments include adaptation of emerging technologies into space, like artificial intelligence and the internet of things, cross-collaboration with other fields of industries, and investment in space ventures.

Since then, the number of Japanese space start-ups has increased – from ten in 2018 to more than 50 in 2021. The companies that have garnered some international attention, like the lunar exploration start-up iSpace, successfully raised more than US$90 million in December 2017. The partnership between privately owned entities and government organisations, like JAXA and MHI’s case, has also been a core driving force behind the growth.

Next-generation rocket

More recently, the Japanese cabinet established a $US6.7 billion JAXA fund for the next 10 years in November 2023, aligned with Japan’s Space Technology Strategy announced in the same year. The fund is planned to be used for development support, technical demonstrations, and introductions of commercial advanced space technologies. In February, the Space Policy Committee set three main categories of support – satellites, space exploration, and space transportation.

For Japan, competing for shares in the commercial space market is a strategy to overcome its economic downturns and show its competitiveness in cutting-edge technologies.

The challenge will be whether the private sector will be able to sustain on its own without the government’s funding by 2034.

“The future of Japan’s space industry and domestic economy depends on whether the private sector can utilise this 10-year strategic fund as a means to move away from dependence on government funding to establish industry-led space ecosystems, and whether policies align perfectly with the direction of the private sector,” Yui Nakama, a European Space Policy Institute fellow, was quoted as saying by SpaceNews.