Digital nomads are becoming more and more common. The desire to work independently and remotely, combined with the opportunity to earn a living by travelling, is an approach spreading everywhere and with a high growth rate in Europe. The trend accelerated with the Covid-19 pandemic, with the closure of offices for long months that convinced many people that it is possible to work while giving up the usual desk.

For an ever-changing category, drawing up numbers and classifying the many different souls within it is very difficult. Since there are no rules to uniquely define what the digital nomad is, after all, it is impossible to enclose those who choose to work under a rigid label by breaking away from the traditional mode.

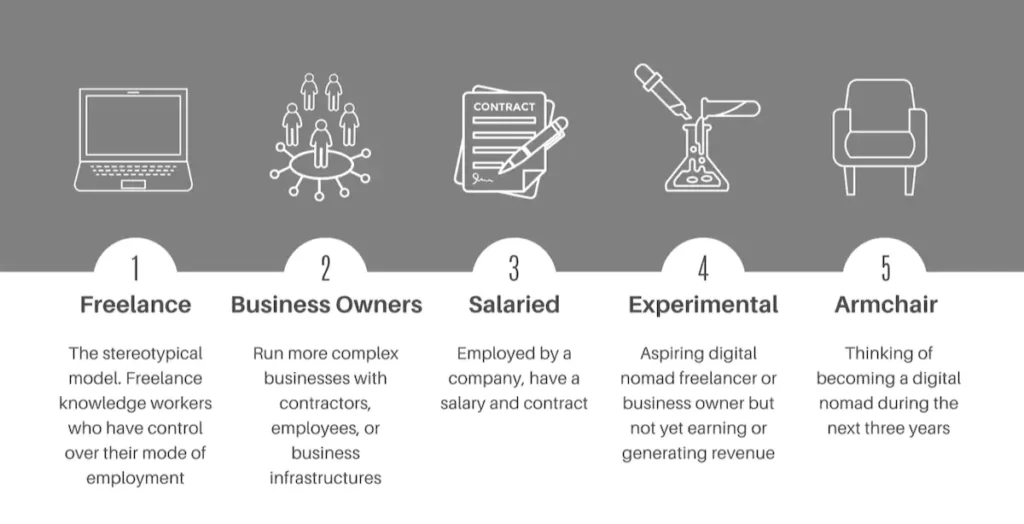

The many different souls of digital nomads

The mix of information and the evolution that has taken place during the past few years as to how they work and travel has led to the emergence of five typologies of digital nomads. I have already covered the topic in my Smart Corner, recounting how more and more countries are opening their doors to worker-travellers and drawing up a sketch of those who work remotely. This time we try to outline different ways of being a digital nomad, taking a cue from a study authored by anthropologist Dave Cook, who drew on various research in recent years to show how the definition has taken on more meaning, thanks to creative minds that have found their balance between life, work and leisure.

Freelance digital nomads

“The traditional and stereotypical type of digital nomad, the subject of most pre-pandemic research.” Until 2020 for Cook, this group brings together most freelancers capable of supporting themselves by working independently, with personal time and methods, untethered from the office routine (starting with working hours 9 am-5 pm). Bloggers, digital marketers, photographers, writers, virtual assistants, programmers, designers and virtual coaches are famous figures who can practice their craft anywhere. They are still numerically the most significant slice of the pie representing the digital nomad, but they are growing less than other newer groups, on the rise after the pandemic.

Digital nomad business owners

“They are digital business owners and run more complex businesses than qualified freelancers.” This is because, in addition to procuring clients and fulfilling their requests, they are dealing with “contractors, employees, and product inventories.” However, they must also forecast and build business systems and infrastructure to make the entire business work. They are a growing group, as they bring together business owners who want to break away from the physical point and focus exclusively on the digital market, but also freelancers who aspire to the quantum leap in ambition and revenue and are starting their own companies to achieve it. Digital, of course.

Salaried digital nomads

Remote workers who work for a specific company can operate remotely and move to different countries within a year. Cook puts employees who move to at least three countries in this group, and they are the fastest growing category, as the upheaval following Covid-19 has convinced large companies to support employees, giving them more freedom that generally makes them more productive than in the past. Considering only the United States, paid digital nomads increased by 42 per cent between 2020 and 2022.

Experimental digital nomads

Only those who want to become digital nomads have yet to because they need the income to support their lifestyle. That is why they are experimentalists; that is, they try to trace the life of a digital nomad in the hope of becoming an integral part of it within a short time. This group includes travellers who start an online business but work other jobs to support it, so they can earn what they need to live on and finance their dream project. “Experimental nomads often meet in coworking spaces, meetups and conferences,” Cook says, referring to fertile places for sharing ideas useful for moving up the ladder professionally.

Armchair nomads

They are the opposite extreme of experimenters, as they work freelance, independently and remotely, earn a good salary but do not travel. Moving elsewhere is a cankerworm, but more often than not, they tend to put off leaving. And in doing so, Cook points out; they influence where they live, as “between coworking and coliving they have an impact on urban planning and housing supply, increasing demand for short-term rentals and thus gentrification.” It is technically wrong to call them digital nomads precisely because they remain fixed in one place, yet they represent the first rung of the ladder they climb when they pack their bags.

In the face of a valuable overview such as the one Cook proposes, perhaps more emphasis should be placed on displacement and correlating it with the individual’s chosen mode of work when discussing digital nomadism. A good key may be how and how much the digital nomad travels, with a division based on that aspect. On one side is the worker who travels full-time; on the other, the nomad who travels for a few months a year; in between is the one who instead plans a fixed-term stay (12-18 months) before looking elsewhere or settling permanently in their host country.