The battle for democracy: how social media challenged Yoon’s martial law

South Korea’s political landscape has been in turmoil since 3 December.

President Yoon Suk-yeol narrowly survived an impeachment motion introduced on Saturday following his attempted coup d’état. This included declaring martial law and sending armed soldiers into the National Assembly and the National Election Commission. His actions left many in shock, as they evoked memories of the military-backed dictatorships of the 1970s and 1980s.

The motion to impeach Yoon on Saturday, after 105 members of Yoon’s conservative People Power Party (PPP) boycotted the vote, leaving the 300-member National Assembly short by 8 votes. The opposition Democratic Party has condemned Yoon’s mobilisation of the military as “unconstitutional” and “illegal”, vowing to introduce a new impeachment motion on 14 December. Meanwhile, the PPP has called for Yoon’s voluntary resignation next year and plans to manage the President’s duties in coordination with the incumbent Prime Minister, Han Duck-soo.

As of 10 December, Yoon is banned from leaving the country, and the National Assembly passed the bill on special counsel investigation into his insurrection attempt.

Following Yoon’s actions during the first week of December, many South Koreans have united in opposition through the power of the internet, particularly social media platforms like X (formerly Twitter) and YouTube. Thousands have taken to the streets, demanding the restoration of their democratic system and the removal of President Yoon.

Live updates of martial law takedown on social media

Yoon declared martial law via a terrestrial television broadcast in the evening. Shortly after the TV address, thousands of people shared screen captures of the broadcast or breaking news articles on their accounts. “The Martial Law” quickly became one of the top trending topics on X, with more than 1 million posts about the news within less than an hour.

Search engines that provide live news updates, such as Naver and Daum, experienced a dramatic increase in traffic, leading to temporary server maintenance issues. With people fearing government scrutiny, messaging and social media platforms operated by international service providers, like Telegram, surged in popularity, rising to third place in the top messenger apps in the country on the App Store the same day.

What’s particularly noteworthy is that the majority of people became aware of the declaration through social media rather than Yoon’s television broadcast. In a country where the number of TV viewers among younger generations has been steadily declining – potentially due to the rise of video streaming services like YouTube – many learned about the news via social media. According to a recent survey, more than 70 per cent of people in Korea encountered the declaration through posts on social media.

Politicians also spread the news through social media. A clip of DP spokesperson Ahn Gwi-ryung fearlessly grabbing an armed soldier’s gun during a stand-off between citizens and the troops at the National Assembly went viral, amassing more than 8.6 million views on X alone and attracting the attention of foreign media outlets.

DP leader Lee Jae-myung, who was the runner-up in the previous Presidential Election against Yoon, hosted a livestream on his YouTube channel, documenting his journey to the National Assembly to oppose martial law. When he climbed the fence to enter the building amidst the chaos, he drew significant attention from X users and other online forums.

Amid the explosive number of uploads, there was also a surge in misinformation. For example, one post, which was reposted thousands of times on X, claimed that Yoon’s military government would impose a curfew, banning people from walking on the streets after 11 p.m. Nevertheless, many users collaborated to fact-check each claim and debunk the misinformation, striving to share accurate details among them.

Calling for improved democracy via social media

Thanks to social media’s information-sharing features and real-time conversations, people were able to organise and mobilise quickly against the military-backed attempt at dictatorship. Following Yoon’s TV broadcast, hundreds of open group chats were formed on Kakao Talk, where participants discussed what might happen next and how to stop martial law.

Across various social media platforms, including newer ones like Bluesky and Threads, users shared details about candle-lit demonstrations calling for Yoon’s impeachment. Although the location of the demonstration was moved from both Gwanghwamun and the National Assembly to just the National Assembly during discussions, an estimated 1 million people attended the protest on 7 December.

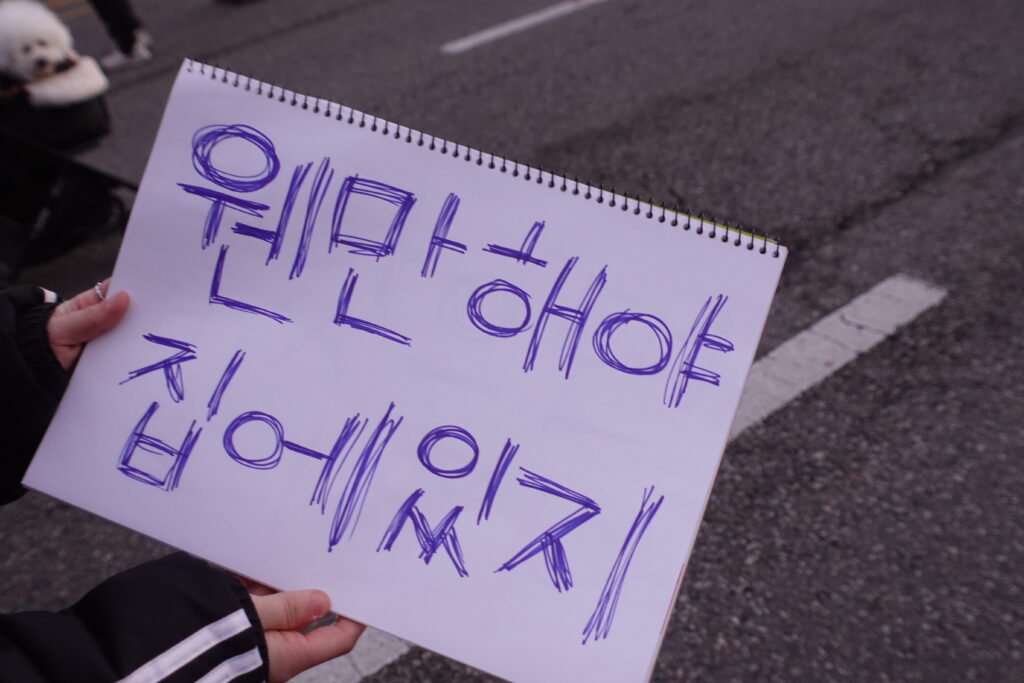

Protest flags featuring humorous catchphrases representing various groups within the community also gained traction on the internet. On X, multiple threads emerged showcasing memorable flags from the protests, including “People who still call ‘X’ ‘Twitter’,” “Introverts,” and “People who came to the protest without telling their parents.“

Maps of nearby toilets and parking lots at protest venues across the country were circulated online. Some individuals pre-paid for dozens or even hundreds of hot meals or coffees at local cafes and restaurants for protest-goers to encourage participation. They shared the locations of these establishments and invited participants to freely take the refreshments that had already been purchased.

The active participation of the K-pop community also came under the media spotlight.

In South Korea, X has traditionally served as a key platform for K-pop fans to connect with like-minded individuals and share information about their favourite bands. With X being one of the most prominent social media forces mobilised during this event, the protests have seen a significant surge in participation from women in their 20s and 30s, who chant the names of their idols and declare, “I will make a better world for you to be an artist.”

Many of the participants brought light sticks, representing K-pop idol groups, which became a major symbol of the recent protests calling for the impeachment of the incumbent government. Concerned that the harsh Korean winter breeze might quickly extinguish candles, the fans opted to bring light sticks representing the artists they admire. Considering that these light sticks can cost between 40,000 and 60,000 won (roughly US$ 27 to 40), one X user remarked that bringing them to the tumultuous protests demonstrated the fans’ strong commitment, “willingly emblazoning their most cherished, brightest items with protest-related printouts.”

Protest flags featuring humorous catchphrases representing various groups within the community also gained traction on the internet. On X, multiple threads emerged showcasing memorable flags from the protests, including “People who still call ‘X’ ‘Twitter’,” “Introverts,” and “People who came to the protest without telling their parents.“

With the impeachment process yet to begin at the National Assembly, reports suggest that anti-government protests will likely continue on the streets for the foreseeable future.

Internet-driven democracy

The ongoing demonstrations against President Yoon highlight the significant influence that social media and online forums wield over South Korean society. When former President Park Geun-hye was ousted in 2017, some reports suggested similar arguments, revisiting the role of internet communities in shaping and advancing political agendas.

“When there was no major political issue, many people focused on the negative aspects of the internet, such as the environment driven by capitalistic or corporate logic-based algorithms,” Lee Gwang-seok, a professor at the Graduate School of Public Policy and Information Technology at Seoul National University of Science and Technology, was quoted as saying.

“However, as we saw in the case of former President Park Geun-hye’s impeachment, the role of social media as a political sphere for discussion will only grow stronger.”