Smart working vs Google: why Google is offering hotel discounts

Smart Working: Google pays its employees and returns some money by giving them a place to sleep. This may sound like a strange initiative, but it is a service designed to make it easier for those who have to endure a long commute to work every day. This in San Francisco is common for most workers in tech companies. Instead of getting out of bed much earlier and making the usual commute, the solution proposed by Big G is to stay in a hotel to zero the distance to the office, with the guarantee of getting more and better rest during the night.

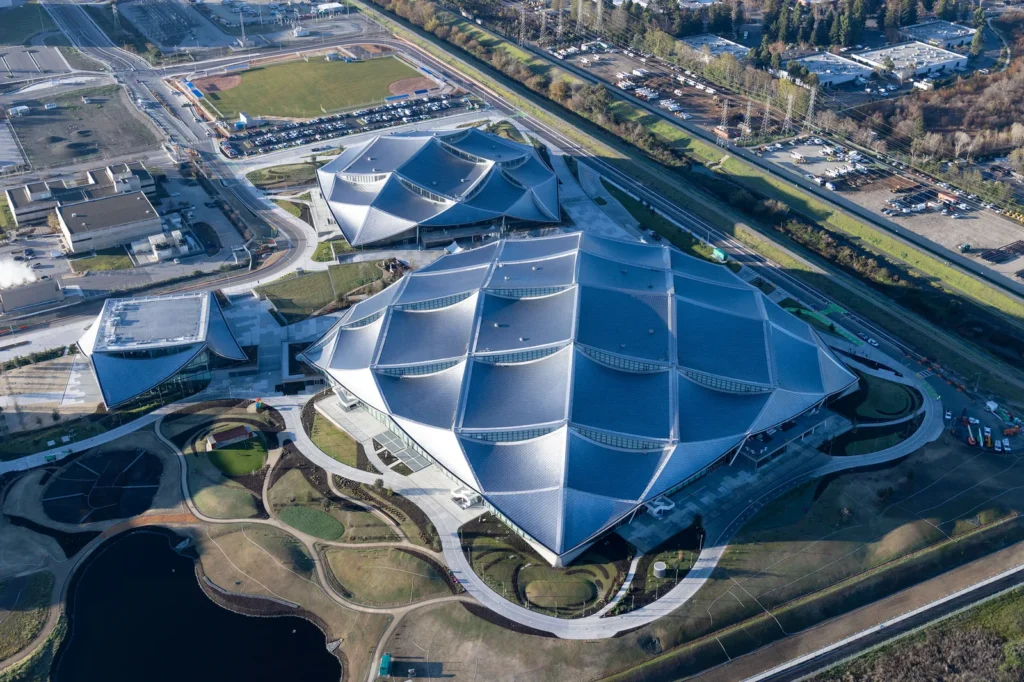

The option appears convenient because Google has activated a promotion for Googlers: $99 per night is the rate for a place in the hotel on the new 42-acre Bay Way campus, which opened in Mountain View in April last year and adjacent to NASA’s Ames Research Center. But is this strategy trying to reduce smart working in general?

How Google is against smart working

Fully electric and with what the company described as ‘the largest geothermal plant in North America‘, the campus can accommodate up to 4,000 people and has been filled by ads teams (the hotel offer is valid only for them). The company’s special offer aims to push for employees’ return to the office, reduce the number of smart workers and apply hybrid work on a large scale. Already last year, Google began manoeuvres to fill its offices, opening a hot front in the face of protests from workers, convinced supporters of the smart working method as the most effective mode of operation for them and the company’s productivity. This is why Big G has recently changed its policy in recent weeks, specifying that office presence will be a factor in employee performance evaluation. Not to mention that in January, the company announced a first wave of cuts, with 12,000 redundancies.

Analysing the context of Google in San Francisco, it is clear to me that having a hotel on campus is an advantage for Googlers because the city offers few accommodations, as well as a system of urban planning restrictions that have contributed to the surge in demand, driving up the prices of houses and flats. For many years, many workers have been forced to find accommodation in the city suburbs and to wake up very early in the morning to go to the office. Smart working has been a game changer, but with the emptying of their offices, all tech companies want to bring their employees back to the office. Putting various benefits on the table, but in this case, it is not Google that foots the hotel bill for its workers.

Employees divided: some appreciate and some protest

Beyond the breakfast and terrace that enrich the proposal, paying $99 per night means spending just under $3,000 monthly. A lower cost than the average city hotel (ranging from $120 to $300 per night), but the idea of staying all day in front of the office is certainly not the best. Then it should be considered that this is a discounted rate valid only until 30 September, after which date the increase will be triggered, although, for the time being, Big G has not announced its hotel prices.

Predictably, the offer has triggered different reactions among Googlers, who are divided between those who applaud the initiative and those who complain that the costs are too high. In the sequence of memes and remarks made by employees in an internal forum viewed by CNBC, there are those who “don’t want to give part of their salary back to Google” and those who instead praise the opportunity because “I pay more and get a lot less for my flat”. “At $60 per night, it would be a great alternative to renting a property,” another employee pointed out. At the same time, a colleague stressed the importance of keeping work and private life separate for a better personal balance.

Many tech companies offer workers the opportunity to sleep in company facilities without turning the office into a dormitory, as Musk did in the past at Twitter’s headquarters. Weighing on Google’s case is the city context of San Francisco, unique and incomparable to other locations. But having to pay to be closer to one’s workplace sounds like an unexpected distortion of a working world that perhaps needs to correct specific dynamics.