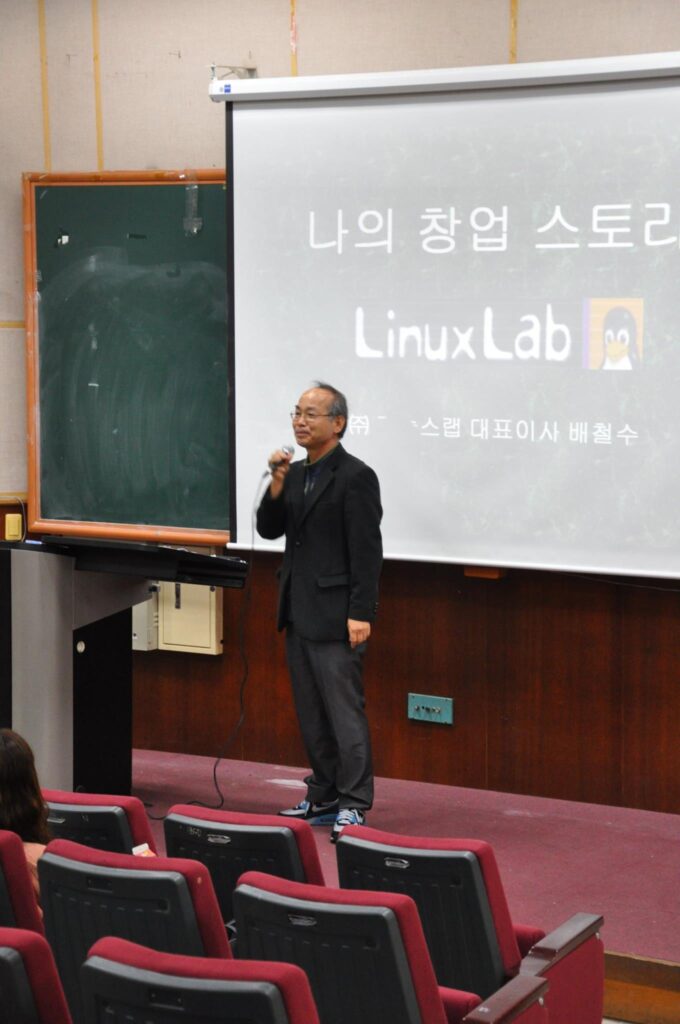

Meet the founder of one of the first VPN providers in South Korea

VPN providers in South Korea: Bae Cheol-su was a huge fan of the operating system Linux, released in the 1990s. Although he did not come from a background related to computer science and had a full-time job at the Korea National Oil Corporation, he felt intrigued by the system and studied it on his own.

When he had to leave his job during the Asian economic crisis in the late 1990s, Bae decided to transition his hobby into a profitable occupation. Bae’s work started with making or maintaining network servers on Linux, including the server of the British Embassy in South Korea.

Since the demand for Linux-run servers was not sizeable compared to other popular operating systems, Bae built a Layer 4 Switch. This device can balance the traffic of servers and networks on Linux to accommodate more customers. Internet cafes and information technology companies were some of the biggest customers to buy the switches he developed.

“But it was hard to make money by selling load-balancing devices,” Bae said during the Google Meet interview with 4i Magazine. “The customers would not contact me unless the devices were out of order after five to six years.”

It was then that Bae received a call from China, asking if he specialises in virtual private networks (VPN), too. “The need for VPN services has been growing in China had been growing there since online games that block access from China, like Lineage, gained popularity,” Bae explained. In the early 2000s, he founded the VPN company LinuxLab, and his focus has been on making VPN-related products and services ever since. “Almost 80 per cent of our sales is from the Chinese customers,” Bae said.

Using LinuxLab’s VPN Service

LinuxLab’s VPN is provided through the Internet Key Exchange version 2 (IKEv2), a VPN tunnelling protocol that offers a secure connection between two peers on the internet. Although many big, international VPN companies offer their services via this protocol, Bae says only a few local companies are adopting this in their VPN businesses.

The company’s VPN-related services can be largely categorised into three: establishing a VPN server, renting a server, and accommodating individual users. For the last business, LinuxLab provides an ID and password for each account for access.

Ways to access LinuxLab’s VPN can vary depending on the types of devices and their operating systems. For example, users who try to access an iPhone would not need to install or download any third-party apps to browse with LinuxLab’s VPN. This is because iPhones have IKEv2 installed in their initial setting. They would just have to put their ID and password and select a server type to connect with LinuxLab’s server. As for Android-operating phones, since their pre-installed IKEv2 system clashes with the company’s server, the company recommends users install the connection software developed by strongSwan and then populate ID and passwords.

VPN providers in South Korea

Compared to other VPN services, one of LinuxLab’s strengths is that it has active servers in China, as the company entered the local market earlier than its competitors. If a company wants to do a VPN service in China, it will need to obtain permission from the government to build a domestic server. However, over 50 per cent of the applying company’s ownership should belong to the Chinese to get the permission, Bae explained. Therefore, many major VPN providers’ servers are in their neighbouring countries, such as Hong Kong, South Korea, and Japan. But as of late, foreign servers are starting to be blocked by the “Great Firewall”.

“LinuxLab has been working in China for quite some years,” Bae said. “We understand the Chinese market situation and how to maintain server operations despite the government’s regulations. Our servers are one of the few foreign company-owned VPN servers that are active in mainland China today,” he added.

Why do Koreans use VPNs more than before

Bae thinks that VPNs can come in handy if you are based in a country that restricts the connection to certain websites. These countries include South Korea, China, and some in the Middle East, he said. “We think that the South Korean government is lenient on internet browsing, but it blocks access to certain websites, for example, pornography or gambling,” he said. “With more people looking for backdoor entrances to visit these websites, VPN giants like Nord VPN started their business in the country, recording fairly big sales.”

Another popular reason to use VPNs is from online video streaming platforms, such as YouTube, Netflix, and Disney+. “When Koreans are outside of the country, they might notice that programmes they have watched may not be serviced with Korean subtitles or voiceovers because they are abroad,” Bae said. To watch these programs in their local language, some users find VPNs to connect with a Korean IP address. What’s worse is that there are also local video streaming services like TVING, Wavve, or SPOTV that block non-Korean IP addresses from accessing their platforms.

“Now people are considering VPNs as an essential product to subscribe to when travelling outside of South Korea if they hope to watch their favourite media content in the local language,” Bae said.

The pandemic also made an impact on the VPN industry, Bae thinks. In the past few years, more people have chosen to stay in their homes instead of going out and interacting with others, and companies urged their employees to work from home to prevent the spread of the virus.

“When you are working from home, using a VPN is a must”, Bae said. “Many became aware of the concept of VPN when their workplaces asked them to download certain VPN apps for work. We sometimes receive calls from people to learn more about VPN services offered by their companies, too. That is indeed a big change.”

Bae emphasised that companies should choose VPNs run by safer protocols with high levels of encryption. “IKEv2 and Secure Socket Tunneling Protocol (SSTP) are some of the safest services available in the market backed with stronger encryption systems, than Point-to-Point Tunneling Protocol (PPTP) or Layer Two Tunneling Protocol (L2TP).”

He also warned about some “free” VPN services, as they may collect users’ personal information for money. “These VPN services earn profit in two ways; one is through posting general advertisements and the other is through customised advertisements, based on the search history of a VPN user,” Bae said. “Not only do they have your personal profile when you sign up on their website, they also gather and sell your browse history to advertising companies.”

Looking out for the future

We hear that the VPN industry has been growing rapidly in recent years, but the internal development of servers and protocols has been stale. Bae explains that only a handful of companies can build new protocols, including Microsoft or Cisco. The concept of VPN protocols may be challenging to comprehend, and even enthusiastic VPN users might not have a full understanding of the service they are on.

To improve their understanding and reach out to a new customer base, LinuxLab hopes to offer easier user interface and designs for its VPN services in the coming years. “IKEv2 is not a protocol that is widely known to the general public,” Bae told the 4i Magazine. “We hope to make a more easy-to-use, convenient system for people who are new to VPN can also browse without bumping into hesitations. That is the biggest goal of ours for the near future.”