AI technology has made remarkable strides, offering solutions to problems we never thought could be addressed by machines. One such innovation is the creation of AI chatbots designed to replicate conversations with deceased loved ones, providing comfort and preserving memories in a unique digital form. This technology, often referred to as “grief tech” or “death tech,” is transforming the way we handle loss and remember those who have passed away.

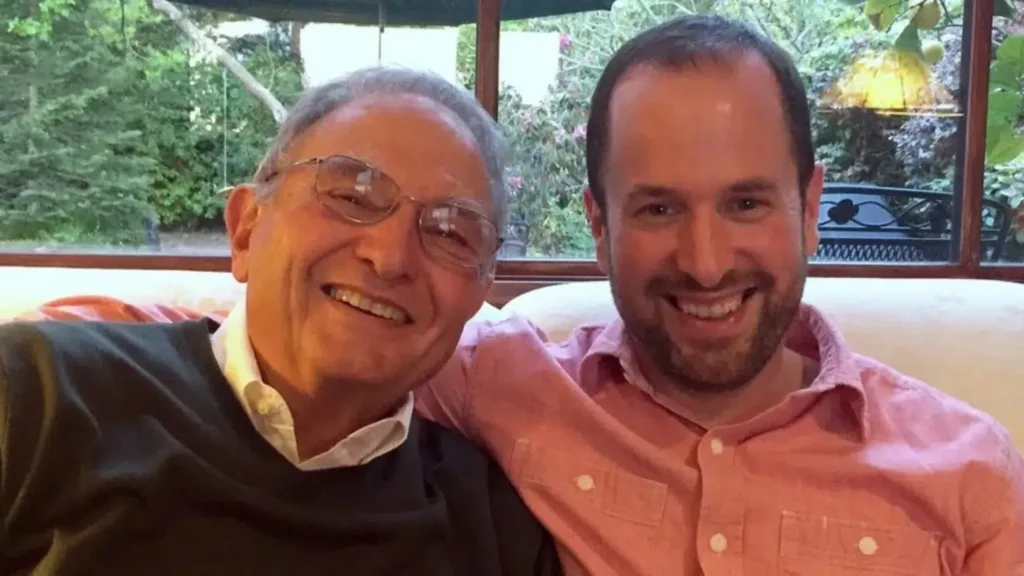

James Vlahos and HereafterAI

One of the pioneering figures in this field is James Vlahos, a businessman from California. In 2017, James faced the devastating news that his father had been diagnosed with terminal cancer. Determined to preserve his father’s memories, James embarked on a project to record extensive audio conversations with his father, capturing his life story in detail. As he delved deeper into the world of artificial intelligence, James had an idea: what if he could create an interactive version of his father using these recordings? This idea gave birth to HereafterAI, an AI-powered chatbot that can converse in the voice of James’s father, answering questions and sharing stories just as he would have in life. James shared his journey with the BBC, explaining how the chatbot provides him with a “wonderful interactive compendium” that keeps his father’s memories vivid and accessible.

Encouraged by the success of his personal project, James turned HereafterAI into a full-fledged business. The platform now allows other users to create similar chatbots for their loved ones, using photos, audio recordings, and other data to craft a digital persona to interact with family and friends. While the chatbot cannot replace the physical presence of a lost loved one, psychologists acknowledge that it offers a form of solace by keeping memories alive in a tangible way.

Grief tech and ethical considerations

The concept of using AI to recreate deceased individuals isn’t limited to audio chatbots. DeepBrain AI has developed a more advanced approach in South Korea, creating video-based avatars that replicate a person’s face, voice, and mannerisms with remarkable accuracy. According to Michael Jung, DeepBrain’s chief financial officer, their avatars achieve a 96.5% likeness to the original person, providing a lifelike experience for users. However, this service comes at a high cost, with prices reaching up to $50,000 for creating a digital avatar.

The rise of such technology raises critical ethical questions. Psychologists like Laverne Antrobus caution against rushing into the use of “grief tech,” particularly during times of heightened emotional vulnerability. The potential for psychological distress is significant, as interacting with a digital version of a loved one can be both comforting and disorienting. It’s essential for individuals to feel emotionally stable before engaging with such technology and to take the process slowly to avoid exacerbating their grief.

Despite the concerns, many see potential benefits in integrating AI into the grieving process. Vicky Wilson, co-founder of Settld, a UK-based platform that helps manage the administrative tasks following a loved one’s death, believes that technology can significantly reduce the burden on the bereaved. Settld automates the process of contacting various organizations to close accounts and handle other post-mortem tasks, saving families time and emotional stress. David Soffer, editor-in-chief of TechRound, highlights how the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the acceptance of technology in handling grief. The pandemic underscored the importance of life and opened up discussions about death, making people more receptive to tech-based solutions for remembering and honouring their loved ones. Soffer emphasizes that while technology can address many aspects of grief, it should complement rather than replace traditional forms of support, such as human interaction and community.

Future prospects

The “grief tech” sector is rapidly growing, with an estimated global value exceeding $100 billion. As AI technology continues to advance, the possibilities for preserving and interacting with memories will expand. However, developers and users must navigate the delicate balance between technological innovation and ethical responsibility. One of the main challenges is ensuring that AI chatbots do not manipulate or cause harm to users. Transparency about the capabilities and limitations of these chatbots is crucial to prevent users from developing unrealistic expectations or emotional dependencies. Furthermore, as AI systems are trained on vast amounts of data, there is a risk of perpetuating biases and stereotypes. Companies must adopt rigorous standards to safeguard against such issues, ensuring their technologies provide a positive and supportive experience.

The story of James Vlahos and HereafterAI illustrates both the potential and the complexities of integrating AI into the grieving process. While technology can offer new ways to remember and interact with loved ones who have passed away, it also raises significant ethical and emotional considerations. As the field of “grief tech” evolves, it will be essential to prioritize the well-being of users, providing support and guidance to navigate their loss. Ultimately, the goal of this technology should be to complement human connection, offering solace and preserving memories in a meaningful way.