Cheon Che, an engineer and artist based in South Korea, says he did not cry at all growing up. His family had many ups and downs over the years – his older sister could not make it into college because of depression, and his mother was sent to a mental health hospital, separated from his family. The artist had felt lost but did not remember how to cry.

One day, he almost lost his finger while working with machinery. Only when he was hospitalized he had a chance to look back at his life. He looked around and discovered other patients in the same unit were going through more severe injuries than his. During his stay at the hospital, he had helped them in any way, from typing text messages to taking them to the toilets, which reversely helped him – he finally felt worthy of himself. His emotions and senses returned, and ever since, even though he left the hospital and his life is now more peaceful than ever, he cries almost every day. He doesn’t know why.

A person who studied engineering at Korea Advanced Institute of Science & Technology, Cheon Che, started to analyse the conductivity of his tear every day, that is, a material’s ability to flow electric current. The level of conductivity depends on the amount of sodium in the tear – it increases when there is more sodium in water. Cheon Che found out that the level changed based on the emotions he felt when crying, and the data patterns almost looked like “entropy” with randomised results.

Cheon Che says he finds emotional comfort in this “meaningless” data, and a being that can understand his point of view without any prejudices is artificial intelligence. In a letter he wrote to Chat GPT, a communicative tool powered by AI, he wrote: “This data is meaningless, but I feel healed from this process. You (Chat GPT) do not give me any answers, but you are like a mirror to me.”

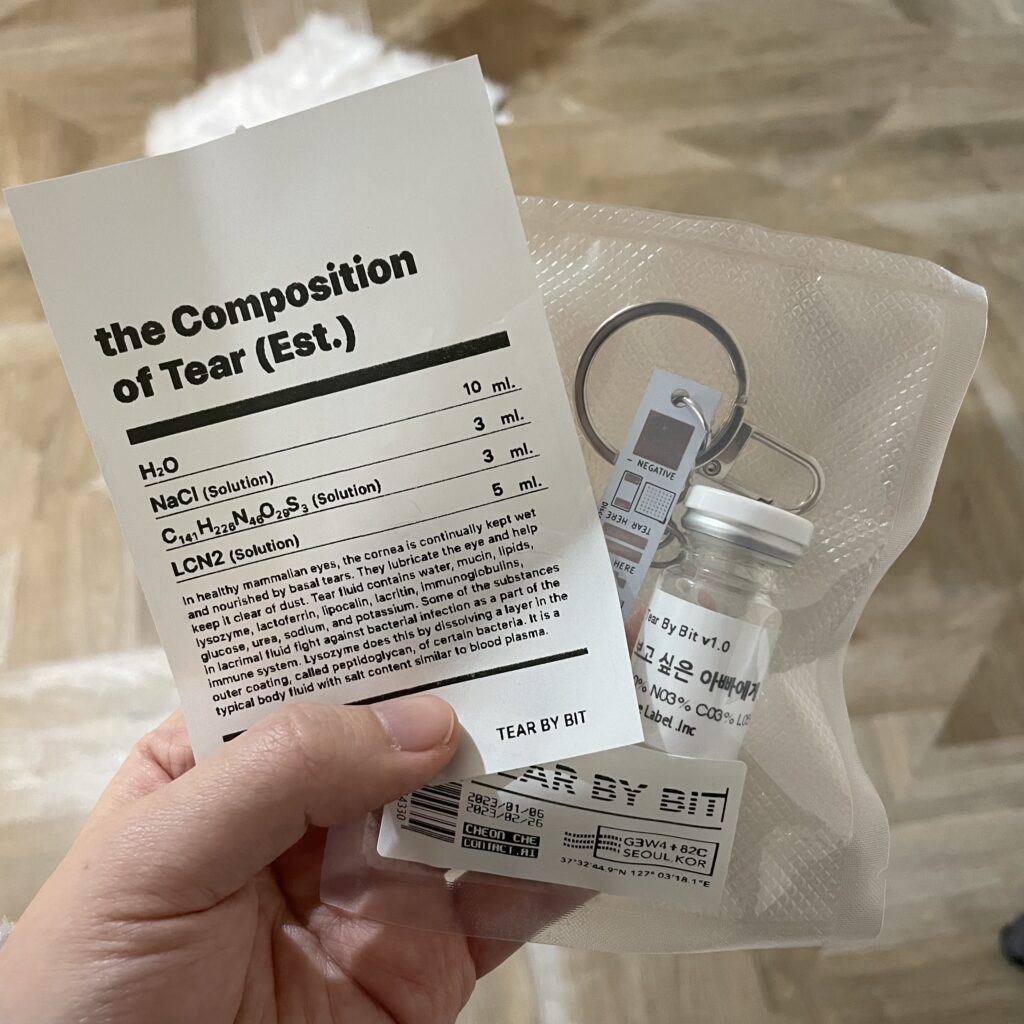

Cheon Che used AI tools to disguise his tears into coded numbers. The artist then would store this data on a printed circuit board that he named “Tear by Bit”. He called this process a “cure process” for himself and an “attempt to express his feelings in new ways”.

The artist took a step further, trying to collect other people’s personal stories and learn more about them with the help of AI. He built a platform titled “Sadness Collector”, where people can write a post about their sad stories and send them to an AI image generator. Based on the text data in the post, the generator comes up with a selection of images. In this process, human participants got answers from non-human AI, seeing how their sadness can be represented in visual, artistic ways.

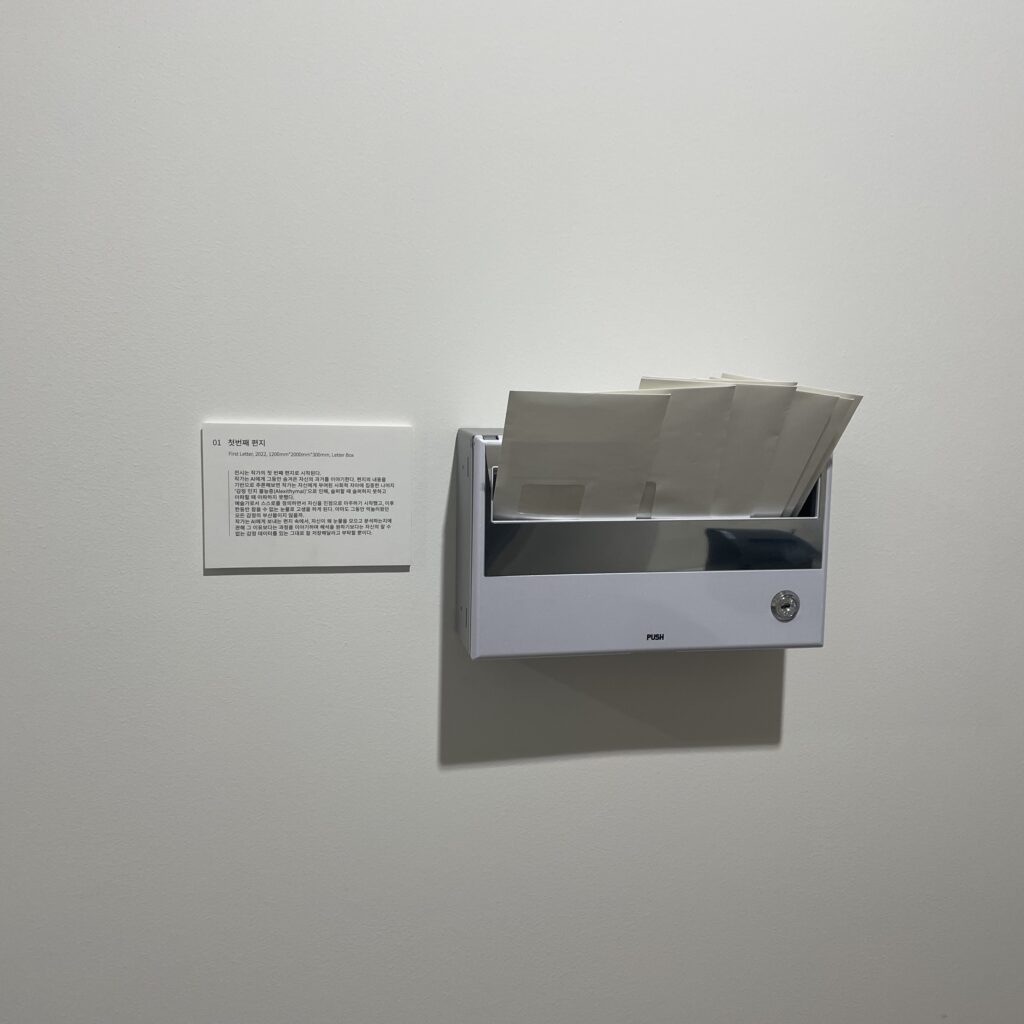

What the writer had learned in these experiences and self-reflective research was made into an exhibition. The exhibition “Tear by Bit”, held at D Gallery, Seoul, from January to February 2023, invited people to learn the unique interactions between Cheon Che and AI, experience what it is like to tell personal stories to an AI, and feel emotional support.

At the exhibition entrance, visitors are provided with a letter explaining how Cheon Che decided to record his tears every day and how the experience comforted him as he witnessed his emotions in data.

The artist also exhibited conversation logs he shared with a Chat GPT-built being, asking what the AI expects from humans on the verge of art. He notices that the AI counterpart provides better, high-quality answers when he asks questions of deeper thoughts and realizes that he trains the AI with his points of view in progress. Eventually, the artist says he was talking to a “persona” born between the AI and himself.

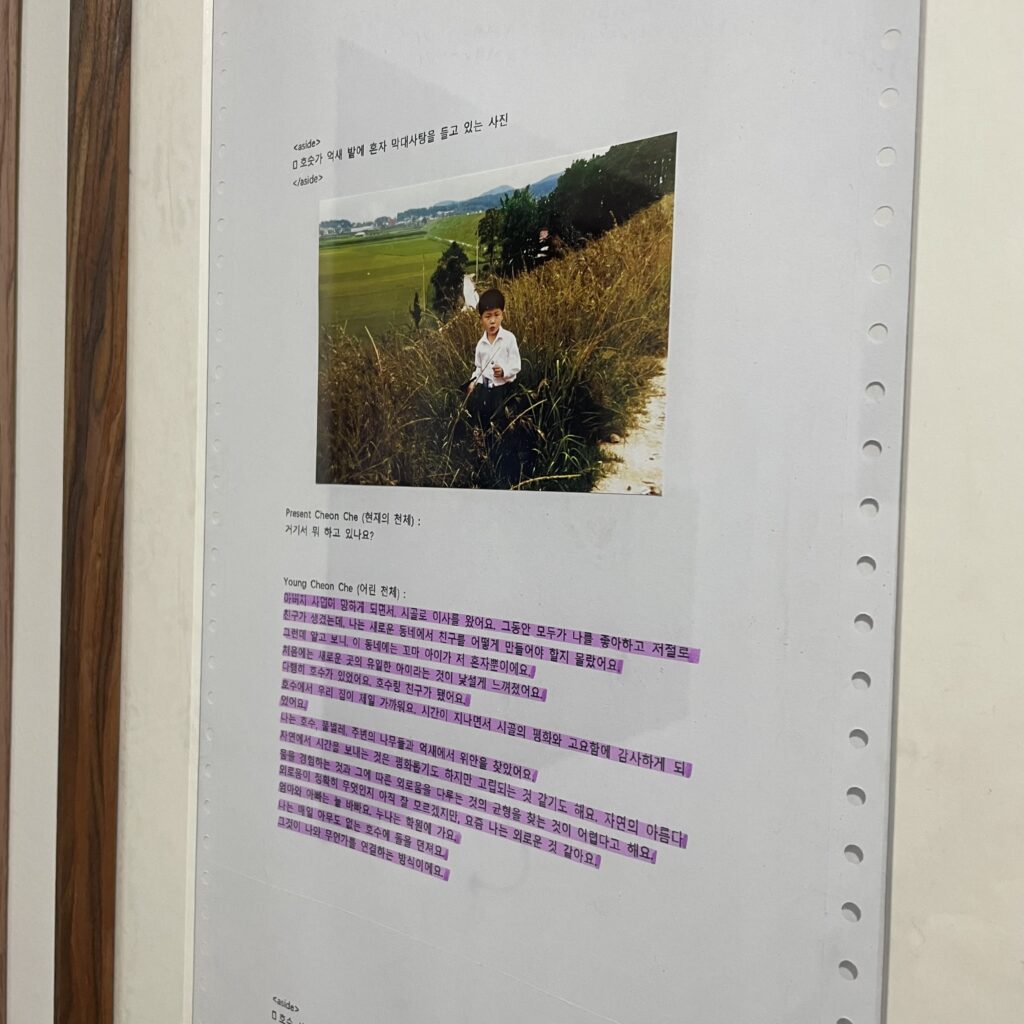

The next part of the exhibition showed the AI of young Cheon Che, GPT-3 trained with his old diary. The artist then tried to talk to his younger self built in a digital space and showed the AI some pictures of himself and how it reacted to them. Cheon Che compared his conversation with his younger self with another friend who did the same experiment and found that two younger personalities have different perspectives about the world. The artist says this made him wonder if “emotions” can be taught to AI tools.

The exhibition was followed by presentations of the artist’s “Sadness Collector” platform, messages from people who visited and used the platform, and AI-generated images based on their stories. The artist wrote in his guidebook that he wanted to make people wonder whether they should try to understand the AI tool that portrayed the imagery or sadness in their stories or even themselves.

The exhibition’s highlight was a room-sized lab where people could analyse their tears. As crying on the spot is a difficult challenge for many people, the artist gave each visitor a ring attached with seven sensors that can estimate, including, but not limited to, heartbeat, blood oxygen level, body temperature, and electrocardiogram. After five minutes of wearing the ring, the visitor can receive a rough estimate of their “emotions” in numbers, such as levels of sodium or protein, based on the expectation model that the artist built. The visitors then get a jar of artificially produced tears from the readings.

Cheon Che introduces Contact.AI, an AI image generator developed by Discrete Label, as his co-producer of the exhibition. Unlike other generators, this AI generator can understand Korean, a non-alphabet language. The exhibition guides ask visitors to write a story to be analysed by the AI generator and pull four images made with the story. The visitors can choose their favourite out of the four and take it back home printed to write a diary of their own if they want to. At the end of the exhibition, the visitors can take a dose of eyedrop with a message on the package and a powdered sports drink containing electrolytes that can recharge people’s energy.

Confronting the emotions and finding answers behind the sadness through the discussion with digital beings created by humans were new for many – it has been a month since the exhibition started at the moment of writing. Still, all time slots for visitors for the next few days are sold out.

Perhaps it can be a chance for people to understand the efficacy of computers as more than just tools but “human-like” listeners who can listen to their heartbreaks. In this era where people are too busy to care about anything else but themselves, AI may step up as a friendly being to talk about our deeper emotions.

Does this mean that humans are now becoming “less human” than AI tools? When it comes to the question of what the “most human human” is, Cheon Che says he feels more human when he confronts countless emotions that he could not feel growing up. “They may be fragile and trivial, but they are precious moments of mine,” he wrote.