Space Law: In recent months, the spotlight has been cast on a declaration by the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, heralding “Universal Internet Access as a Fundamental Right”. It’s an ambitious proclamation, echoing the aspirational tenets of our digital age. However, on closer scrutiny, realizing this vision remains challenged by today’s realities.

A monopolistic stranglehold over cable and broadband services in several countries effectively sidelines many, ensuring that the digital gateway remains a luxury, often solely for the well-heeled or those nestled within urban epicentres. But as terrestrial constraints continue to bottleneck our ambitions, our gaze inevitably shifts upwards, specifically to the expansive satellite network pioneered by Elon Musk’s ambitious venture, SpaceX’s Starlink.

Currently, Starlink’s constellation promises to connect a quarter of humanity, irrespective of their geographical moorings. But this digital bridge has its toll. Access fees oscillate between a modest $100 to a dizzying $2500, contingent on the user’s locale and requirements. As Starlink carves its niche in this space-age frontier, it’s not without competitors. Numerous enterprises are propelling their ambitions into the Low Earth Orbit, all resonating with Mark Zuckerberg’s enduring aspiration of weaving a “connected world”.

A long-time vision now almost accessible

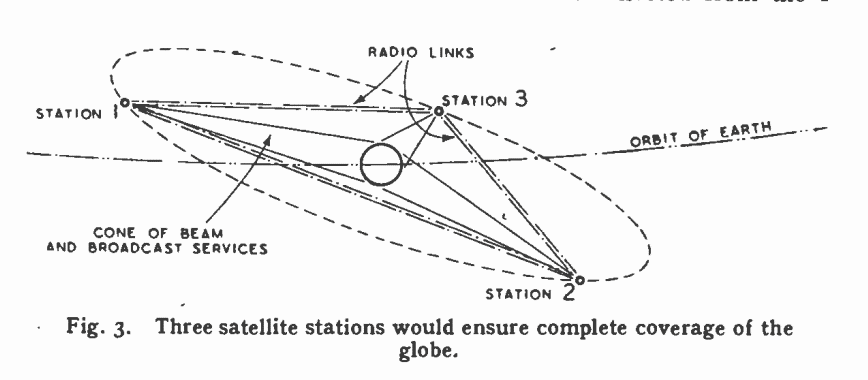

During the 1920s, a time of burgeoning technological aspiration, science fiction literature painted a picture of a globally interconnected world via spatial solutions. It’s fascinating to think that the nascent concepts from these novels bear an uncanny resemblance to our current satellite internet connectivity systems. Notably, in 1945, Arthur C. Clarke, at that time a young officer in the Royal Air Force, ventured into nonfiction to propose the radical idea of a communications satellite. In an article for Wireless World Magazine that October, Clarke introduced the concept and provided a detailed schematic of how these pioneering satellite stations might come to life. Clarke’s visionary projection was that merely three strategically placed satellites would be enough to connect every corner of our planet.

As we assess our present-day tech landscape, we realize that while we’ve made leaps in satellite technology, we’re still striving to realize the full scope of Clarke’s 1940s dream. Starlink, one of today’s leading forces in satellite internet services, has impressively launched 5,000 satellites. However, despite this monumental achievement, their vast array doesn’t cover Earth’s entire surface.

A “new war” to build a constellation of satellites

As U.S. military officials assert the nation’s readiness for potential space conflicts, the real war may unfold much closer to home. Rather than the cinematic skirmishes of “Star Wars”, the contemporary battle is about dominating the low Earth orbit with satellites.

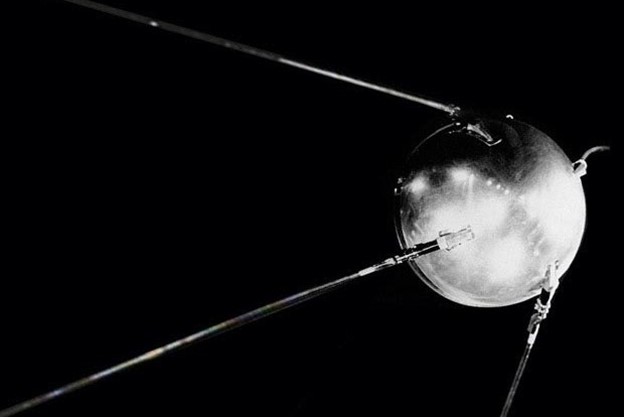

This race to the stars began precisely 12 years after Arthur C. Clarke envisioned a world connected by satellites. On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union marked a monumental achievement by launching Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite. In 1965, the inaugural commercial communications satellite, named Intelsat 1, also known as Early Bird, took flight. By the middle of 1969, Intelsat had successfully established its initial worldwide network by positioning a satellite above the Indian Ocean. This timely deployment allowed for the global broadcast of the first Moon landing.

Today, the competition for control in the low orbit space internet is primarily among three major players: OneWeb, Starlink, and Kuiper. Starlink, a brainchild of Elon Musk, stands out with its capacity to produce up to 45 satellites weekly and launch an astounding 240 satellites monthly.

Space Law

Unlike Starlink’s consumer-focused model, OneWeb – backed by Indian, European, Japanese, and British stakeholders – targets specific industries with tailored global internet solutions.

Kuiper, an Amazon endeavor that has recently partnered with Vodafone, appears to be in the same lane as Starlink. However, while their exact vision remains slightly ambiguous despite recent updates on their website, it’s clear that their services are set to launch by July 2026. This raises the question: Will Kuiper’s late entry allow it to globally compete and potentially overtake Starlink? The future remains uncertain.