Decking out your favorite League of Legends champion with the latest skin or buying a Fortnite dance emote is a seen as perfectly normal nowadays. Microtransactions, be they cosmetic or otherwise, have become an integral, if unfortunate, part of many games.

Yet, just a decade or so ago, spending real cash on in-game items or mechanics was a rarity. After all, why buy a digital item in a game that you might not play a month down the line? So, we are left with the question of how in-game spending became so common. Many point the finger at mobile games, but gaming microtransactions have existed long before them. In fact, they didn’t even popularize or normalize the concept. That award belongs to Facebook games.

A history of microtransactions

You’d be forgiven if you thought that microtransactions or in-game purchases were a modern invention. The truth is that they existed as early as the 1990s. One example that employed pay-to-win microtransactions is Double Dragon 3: The Rosetta Stone. The arcade game had you insert extra coins to buy powerups, weapon upgrades, and even to access special characters.

More than a decade later, this type of monetization slowly crept its way onto PC and console games. MMORPGs were among the first to sell cosmetics items and upgrades for real cash, but there is one infamous moment that will always be remembered in gaming history. If you were a gamer at the time, you’ve probably heard of the horse armor scandal. Developer Bethesda added extra content to its Oblivion game on Xbox, with the first DLC containing nothing more than cosmetic horse armor. It could be purchased for $2.50.

Nowadays, this addition would be seen as mundane, completely unworthy of attention. However, at the time the cosmetic DLC riled gamers up. It was widely mocked online, and few saw the point of an item that did nothing but make your horse prettier. However, the notorious horse armor would be among the snowflakes that caused the avalanche of microtransactions that followed.

Other triple A publishers weren’t shy to follow Bethesda’s example. EA opened a Sims store in 2008, and Valve added hats to its hero shooter Team Fortress 2 in 2010. Nevertheless, they weren’t shameless enough (yet) to put non-cosmetic items or mechanics behind a paywall. Facebook games, on the other hand, were laying the foundations of brazen in-game purchases that sent the unprepared down an addictive spiral.

Facebook games and social pressure

In 2008, when smartphones weren’t nearly as mainstream as they are today, Facebook games solidified the common “mobile” format we know today. Before Clash of Clans and Candy Crush, Farmville and co reigned supreme.

Early Facebook adopters might remember Pet Society – one of the microtransaction pioneers that made its way onto the social network in 2008. An innocent Tamagotchi-like game, Pet Society had you take care of a virtual pet of your choosing. You had to bathe and feed it, but also decorate its house, choose different outfits for it, and of course, visit friends’ pets. There were some mini games such as fishing and racing to level up your pet, but they were not the main focus of the experience.

The true competition came from the game’s social elements – who had the best dressed pet, the latest hairstyle, and the fanciest furniture. Pet Society encouraged this. It rewarded you for visiting friends with coins, feeding the “keeping up with the Joneses” complex. It was a very effective strategy to get people to buy into its premium currency too. Exclusive items could only be bought with Pet Society Cash, which in turn needed to be bought with real money.

Of course, you could play Pet Society without spending a single real cent and still enjoy it, but the premium currency was certainly enticing. Who didn’t want to impress visiting friends or get the same cool exclusive items as them?

Fear of missing out was also employed to great effect. Pet Society Cash items were sometimes available only for a limited time, as was some of the best-looking holiday themed furniture. It made for a hard to resist proposition, especially when the game was at its peak popularity.

Nevertheless, while Pet Society did employ some sneaky microtransaction tactics that took advantage of its social nature, it wasn’t tailored to be nearly as shallow or as exploitative as games that followed.

Farmville, or gaming as a chore

Once named one of the 50 worst inventions by Time magazine, Farmville is the game that truly took gaming microtransactions to the next level of awful. It landed on Facebook in 2009, at a time where games like Pet Society had already laid the foundations of selling premium currency.

Farmville was an extremely basic farming simulator in which users planted crops and took care of virtual animals. The gameplay was barebones, with little strategy or competitiveness involved. In fact, it was little more than a series of virtual chores. So, how did Farmville become the biggest game on Facebook? It used a plethora of psychological tricks to keep users coming back for more. In the process, it normalized some of the most exploitative microtransactions common today.

The Zynga game created a problem and sold you a solution. Plants didn’t grow very quickly – some like corn needed as much as 3 actual days. However, you could speed the process up by paying real cash. You could also increase your harvest with premium currency items. Spending money wasn’t reserved for cosmetic items anymore – it was part of the core “gameplay”. This persuaded impatient players to pay for immediate gratification. Since then, this monetization tactic has become a mainstay of many popular mobile games such as Clash of Clans.

Farmville required consistent commitment too. Your crops withered after a certain time, so you needed to open the game every few hours if you didn’t want to miss out on your virtual harvest. This tactic exploited the common fear of missing out and the sunken cost fallacy. Even if they weren’t having fun, some players returned so they didn’t feel like they wasted their time, even if that’s exactly what they were doing by playing Farmville in the first place. It kept players in a repetitive, addictive loop that demanded their attention.

Moreover, Farmville seemed to have taken lessons from games like Pet Society too. It utilized the social platform to its full potential. Games could post on players’ timelines and send notifications, and Farmville was relentless. You were encouraged not only to visit friends’ farms but to invite them to your own. Friends could then help you by watering and fertilizing your crops, and you earned money by visiting their plots. The more friends you had, the better. This meant that even if you weren’t terribly interested in the farming sim, you were bombarded with Farmville spam every time you logged on to Facebook.

The addictive nature of microtransaction-filled games

The peer pressure was certainly hard to ignore, and the peak number of 34.5 million daily active players speaks for itself. So does Zynga’s revenue. In 2013, the company hit $1 billion of in-game revenue from Farmville alone.

Unfortunately, its meteoric rise came at a real cost to players – not just in wasted time, but in cash. Of course, no one forced them to spend money to grow virtual corn, but it’s hard to deny the addictive and exploitative nature of the game when there were people going in debt over it. In one case, it was a 12-year-old student who spent more than £900 on his mother’s card. Zynga and Facebook refused to refund the money. Adults have admitted to spending thousands on Farmville too.

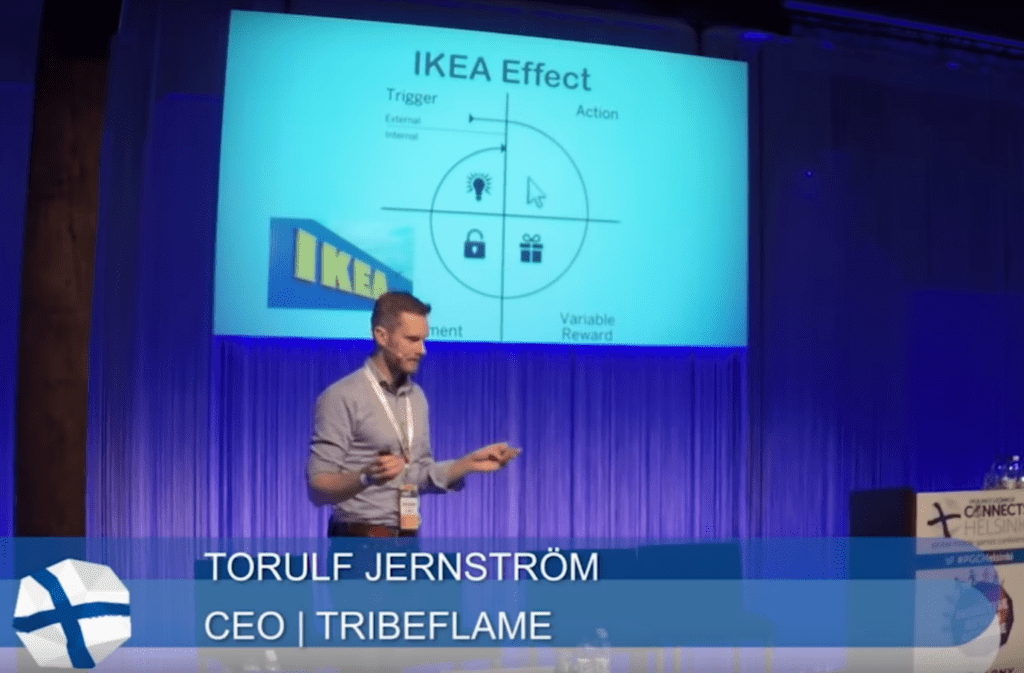

In fact, an exceedingly small percentage of any given “freemium” game’s playerbase spends any money. The ones that pay large sums are few and far between and have been given the derogatory “whales” nickname by the industry. As the now infamous Let’s go whaling talk by mobile games CEO Torulf Jernström points out, exploiting so-called whales is not an accident. It is an intentional part of the design that plenty of games have since adopted.

Farmville didn’t invent this predatory approach to monetization, but it certainly normalized it to a very large audience. After the success of these Facebook games, many developers, including very prominent triple A studios, adopted and even evolved these dirty monetization tricks.

Lootboxes were a very unfortunate but predictable next step. Studies have since linked them to problem gambling and addiction, and lawmakers in various countries have called for their regulation. However, we are unlikely to see lootboxes disappear completely anytime soon. Studios like Activision Blizzard and EA make billions from these microtransactions every year.

And we have Farmville and other Facebook games to thank for that. Once seen only as silly casual titles, they’ve changed our relationship to in-game spending forever. Without them normalizing microtransactions, who knows if we would have had colorful Fortnite skins, games like Candy Crush, or Overwatch lootboxes.

Farmville went offline in December 2020 after an 11-year run, but the ripples of its impact on the gaming industry will be felt for a long time to come.